DISCLAIMER: NOTHING ON THIS PAGE IS A SUBSTITUTE FOR PROFESSIONAL MEDICAL ADVICE. PLEASE CONSULT AN EXOTIC ANIMAL VETERINARIAN IF YOUR PET IS SICK.

Nidovirus has been one of the most challenging and painful things we’ve had to deal with as reptile keepers. The pain has come from many places—sick animals, lack of resources, and other people.

When other people found out we had nidovirus in our collection, we would get a few typical reactions. People who knew of it in passing were the easiest to talk to. Then some people sort of heard of it but hadn’t dealt with it personally and wouldn’t take us seriously—in both directions, too! Some didn’t acknowledge a concern and others balked at any sort of “experience” we had and treated us like pariahs. Now, I get that last one, but those people are probably the most harmful elements in the reptile community, in terms of sharing knowledge and avoiding the propagation of misinformation.

I have several nidovirus stories and I might share them here too, but right now I just want to focus on what we learned from it.

1) Not every snake with nidovirus has to die. In my experience, there are two kinds of snakes that get nidovirus. One kind of snake will be chronically sick and nothing ever seems to go right. Sometimes they get an infection and you treat it and initially it seems like you might finally have a break but, nope! They’re sick again, and when you look back you struggle to remember when they weren’t. The other kind of snake might be more susceptible to getting sick, but they do respond to treatment. They can be healthy and strong and when they do get sick it can be the weirdest random thing, like a heart infection or a slightly enlarged eye. They get better and move on. They can be made sick, but kept in proper conditions, they often don’t.

2) Stress makes it worse. Lack of proper environmental conditions, lack of airflow, too small a living space—these things can all aggravate a snake with nidovirus and make them more likely to fall ill. Truly, any otherwise healthy animal can fall ill under these conditions. Breeding them can do it too. Breeding is a very stressful event for the body. If you have a nidovirus-positive animal, consider not breeding them. These animals thrive on stability, routine, and proper conditions.

2.5) And about babies and Nidovirus-- If you do have babies, our current understanding is that the virus lives on the eggshells initially but the babies are unlikely to have it out of the egg (Source: Nidoviruses in Reptiles: A Review). Treat them as a separate set of non-nido snakes with their own cleaning equipment.

Babies should be tested 3 times before rehoming or moving into the main collection (we kept our green tree babies until a yeast of age anyway to check for spinal kinks; green trees are more safely tested after the year mark, since the test involves restraint and an oral swab)

3) There are different strains. Some can affect multiple species, but some tend not to. When we discovered we had nidovirus in our collection, we had ALL of our snakes tested. Statistically, based on the studies we read, a certain percentage of each species should come back positive. In the case of the green tree pythons, it did: half of our green trees were positive (Source: Investigations into the presence of nidoviruses in pythons).

However, zero of our ball pythons were positive (and we had quite a few). The lab that did our testing was further able to inform us on the strain we had, and it was distinct from ball python nidovirus. The virus strain could still theoretically “jump“ to another species—it just tends not to. In the wild, different species of snakes living in the same area tend to have their own novel nidoviruses (Source: Divergent Serpentoviruses in Free-Ranging Invasive Pythons and Native Colubrids in Southern Florida, United States)

4) Symptomatic nido-positive snakes should have their own cleaning brush separate from the other positive animals. Realistically the antibacterial soap should remove any transmission problems you have between snakes, but it is just another layer of protection for your asymptomatic animals.

5) Proper procedures can protect your nidovirus-negative animals. Keep the non-nido snakes in a separate room. Make sure their cleaning supplies are separate. When you scrub bowls, use antibacterial soap on every bowl. The feeding tools should be separate too but it will probably suffice to feed the nido-positive animals last and sanitize the things by washing them with antibacterial soap and throwing them in the dishwasher.

Note: Any handling and cleaning (daily checks, poo removal etc) of nido-positive snakes should always be done last. Then, take a shower. In lieu of a shower we would sometimes wash our hands (a real handwashing, like you would in a medical facility) and change our clothes. Our green trees were all on the same ventilation system in an open floor plan house. Our negative snakes stayed negative for the entire five years we kept positive and negative snakes. It can be done.

6) You still shouldn’t take your nidovirus-positive snakes to public places where there are other reptiles. Any person who handles your positive snakes should be made to wash their hands with antibacterial soap before and after handling (before is for the snake. After is for the person/transmission control).

You have to be mindful of where the animals go and what surfaces they climb on. Many surfaces can be sanitized by washing with antibacterial soap. Nidovirus is not well-tested specifically, but similar viruses like coronavirus can give us an idea of how long it can live outside the host (Source: Nidovirus FAQ, 2018) So sometimes just waiting an appropriate amount of time may be enough.

Porous surfaces tend to be a less favorable environment for some of these viruses (Source: Why coronavirus survives longer on impermeable than porous surfaces). However, it’s easier to keep the animal off of surfaces that are hard to clean.

7) Have a cleaning plan in place for dirty bowls and ornaments. We stopped using things like cork for our snakes because they were hard to clean. Anything with feces on it was taken outside immediately until it could be cleaned. Then it was sprayed with 10% ammonia* (this was actually to kill coccidia, which is simply the toughest thing we’ve encountered). Then it was soaked in a water vinegar solution overnight. Then it was scrubbed with antibacterial soap.

We did not have bowls separated once they were scrubbed and cleaned. All bowls went back to the “clean bowl” pool. Before that, though, everything was kept carefully separate. If an ornament needed just a bit of light scrubbing, it was with a specially designated nido-positive brush and promptly returned to the animal’s enclosure afterwards.

Note: lack of availability has led us to replace the 10% ammonia part of our cleaning process with a 1:20 F10 solution (Source: F10 CL Veterinary Disinfectant)

8) We tested our enclosure sanitation process. After our nidovirus-positive snakes were moved out, enclosures were wiped down with a wet paper towel, then Clorox cleaning wipes. Then they were hand washed with antibacterial soap and a sponge. Then they were wiped again with Clorox wipes when dry and, finally, once more with wet paper towels to prepare them for next use. Glass doors were washed with antibacterial soap and put back. We also let the enclosures sit for a couple weeks before using them.

Every swab we had tested along this process after the initial clorox wipe down came back negative. (Note that enclosures sat for about 2 weeks before we cleaned them). The additional wipe-downs may not have been necessary, but we wanted to be careful. Also eco earth gets everywhere and it literally takes that many passes to get rid of it all.

It can be done. It can be done. However, it is really hard to keep all the animals separate. With non-nido snakes in the house, our positive snakes didn’t get handled super often. Actually our negative ones didn’t either. For one, we were worried about disease transmission. For the other, we were worried they’d somehow pick up the virus anyway. So it is better to have one or the other, positive or negative. But it’s hard to rehome snakes with nidovirus to somewhere they will be cared for properly and safe from the pet trade. And you love the ones you love. So, you can use these guidelines to build a plan and protect your animals.

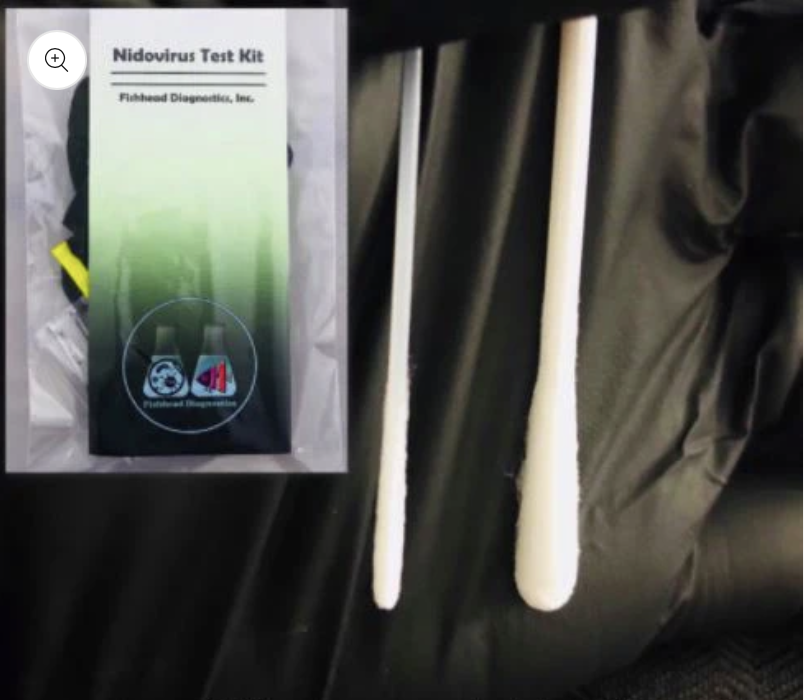

Notes on testing: Fishhead Diagnostics does nidovirus PCR testing. They have regular swabs and micro swabs for smaller animals. You can order test kits here: Fishhead Diagnostics Shop

You will need to physically restrain your animal to swab them. I recommend having 2-3 people on hand—one to restrain, one to take the sample, and one to accept the sample and seal it in the specimen bag.

References:

Blahak, S. et al (2020). Investigations into the presence of nidoviruses in pythons. Virology Journal 17:6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-1279-5. Retrieved from https://virologyj.biomedcentral.com/counter/pdf/10.1186/s12985-020-1279-5.pdf.

Chatterjee, S. et al (2021). Why coronavirus survives longer on impermeable than porous surfaces. Phys Fluids (1994). 2021 Feb 9;33(2):021701. doi: 10.1063/5.0037924. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7978145/#:~:text=Notably%2C%20earlier%20virus%20titer%20measurements%20revealed%20that,surfaces%20such%20as%20paper%20and%20cloth%20than

Maillard JY (2013). Antimicrobial Spectrum of Different classes. The Center for Food Security and Public Health. Retrieved from https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Disinfection/Assets/AntimicrobialSpectrumDisinfectants.pdf

Meadows Animal Healthcare (2022). F10CL Veterinary Disinfectant. Retrieved from https://www.meadowsah.com/f10cl-veterinary-disinfectant#:~:text=*%201:50%20is%20recommended%20for,100%20(10ml/litre).

Parrish, K. et al (2021). Nidoviruses in Reptiles: A Review. Front Vet Sci. 2021 Sep 21;8:733404. doi: 10.3389. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8490724/

Tillis, S. et al (2022). Divergent Serpentoviruses in Free-Ranging Invasive Pythons and Native Colubrids in Southern Florida, United States. Viruses. 2022 Dec 6;14(12):2726. doi: 10.3390/v14122726. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36560729/.